The History of Lyapunovia

“Lyapunovia: Displaying the Juiciest Object in Mathematics.

Lyapunovia is a mindbogglingly colorful program that makes pictures from a simple mathematical formula … offering you everything you ever wanted in visual representation of mathematical abstractions.”

-Me in 1992.

This new version came about when I saw that a modern computer – or phone – can easily render a fractal like this in real time using the graphics card.

In this new version, I focused on making the user experience fun, on making it pleasurable to navigate around the fractal image. I have also animated the fractal a bit, so the goal is not to arrive at the final image, but to explore a strange animated object.

Backstory

Lyapunov Space fractals were created by Mario Markus in the late 1980’s, and probably popularized by Dewdney’s 1991 article in Scientific American.

and probably popularized by Dewdney’s 1991 article in Scientific American.

Having read the Scientific American article, I wrote the Lyapunovia fractal program for the Commodore Amiga in 1992-93. This was just around the peak of shareware, and users could physically mail me payment for a full version of the program, which I’d dutifully send them on floppy disks. Version 1.5 was released the following year, now supporting new Amiga 1200 and 4000 computers with their fancy new graphics chipsets, and switched to a more convenient donation model. (Here is the original readme file.) I probably sold and received literally *many dozens* of contributions, so I was happy.

After that, a made a small version for long gone BeOS, and dabbled in a PC version.

Lyapunovia had a weird role in my life. It made a tiny bit of money for a poor student, but it also heavily distracted me from actual studying, which in some ways would have been better for me, yet I got hired by my future multimedia workplace MouseHouse because they’d seen the program and called me up. Going back to Lyapunovia gives me an intense feeling of where it was made, “while watching the tiny little bit of blue sky I can see from my room if I push my head flat against the window and look directly up”, as the readme file says.

My later life has become something else – writing books about video game theory, occasionally making games, and continually teaching students to make, think, and write about video games.

My original training though, just before Lyapunovia, was in demo culture, and from that I probably brought the idea that programming (which I enjoy) can also be visible and understandable to non-programmers as well. I have mostly channeled this into games, but why not try the fractal thing gain?

What do fractals mean?

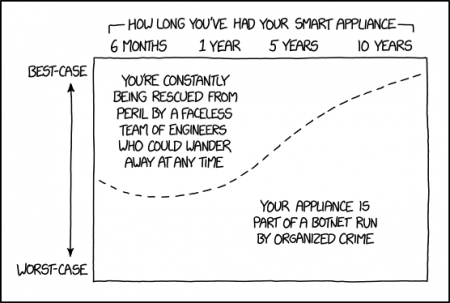

In their 1990ish heyday, I think fractals represented both the future, modern technology, and then-new ideas of chaos and emergence. Today there’s something retroish about them. Yes, we know that small formulas can create complex patterns, but the actual speed of modern computers (coming here from the graphics card of your device) makes fractals immediate in a way they were not.

modern technology, and then-new ideas of chaos and emergence. Today there’s something retroish about them. Yes, we know that small formulas can create complex patterns, but the actual speed of modern computers (coming here from the graphics card of your device) makes fractals immediate in a way they were not.

Clearly, I am making choices here about how to represent Lyapunov Space, but that experience is always one of the formulas having an emergent mind of their own. The fractal doesn’t care about us, and I think this gives a feeling of “sublime banality” – a fractal is vast, infinite, and incomprehensible to our human minds, but it also doesn’t ask anything from us. Other words: Alien, reptilian. It’s a lot like deliberately electronic music, which can be read as life-affirming by showing us how we’re either wonderfully alive unlike the mechanical world, or that we’re wonderfully mechanical as well, or that we are freed from having to fall into established categories. Here’s to that.

Programming then and now

The Amiga program was gigantic, and the mental work was very hard, figuring out how to do things I did not know how to do; writing and rewriting the code, waiting for the program to render, writing the image saving routines, and so on. This was a huge undertaking for me.

This new version was made quickly (~20 hours), it is pretty small, but as is the case with modern web development, it includes 4 entirely different languages – HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and GLSL. The main challenge here has really been to read up on all the documentation, like the weird limitations of the GLSL version I was using. Thanks to WebGLFundamentals for the best WebGL explanations. I have also focused on designing a pleasurable interface that could be used across a range of devices. The idea of the pleasurable interface wasn’t really common in 1992 (except in games).

![delitionist_logo[1]](http://www.jesperjuul.net/ludologist/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/delitionist_logo1.png)

![deletionist-waxy-20130618-212909[1]](http://www.jesperjuul.net/ludologist/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/deletionist-waxy-20130618-2129091-150x150.png)

Get the T-shirt

Get the T-shirt The iPhone 5 case

The iPhone 5 case The cosmetic bag

The cosmetic bag