On Absent Carrot Sticks: The Level of Abstraction in Video Games

Introduction

Figure 1: The player can slice carrots, not make carrot sticks. Cooking Mama (Office Create 2006).

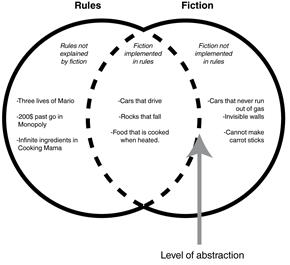

Figure 2: Burning all the cutlets, but Cooking Mama offers infinite replacement ingredients. Here is a naïve question: Why am I not allowed to cut the carrot into sticks? Figure 1 shows the action of chopping carrots in Cooking Mama (Office Create). In this game, the player is tasked with preparing, heating, and arranging ingredients according to the recipes that the game puts forth. While these are all actions that we expect to perform in a kitchen, we can also list an infinite number of other actions that are available in a regular kitchen, but which are not present here: Cooking Mama lets us slice the carrots, but not make them into sticks. In a regular kitchen, we can decide that we do not want to cook after all, and order take-out instead. At first, these may seem like mere technological limitations, but I will argue that they derive from the fact that we are dealing with a game. Finally, Cooking Mama offers us something that we do not regularly experience, namely an infinite supply of replacement ingredients whenever the player burns or otherwise spoils the food (Figure 2). Fiction plays a different role in different video games: some are abstract (e.g. Tetris), while others have a thin veneer of fiction (e.g. Angry Birds), and others feature elaborate fictional worlds (e.g. Mass Effect 2). Given that games by definition allow players to influence the course of events, which contradicts many definitions of narratives, I find that it is preferable to discuss video games using the broader concept of fictional worlds. Since a fictional world may or may not contain a fixed sequence of events, the concept of fiction is a more precise tool for examining video games than is narrative. This also lets us see that video games are Half-real, meaning that they are an intersection of two quite different things: they are real rule-based activities that we perform in the actual world, and they are fictional worlds that we imagine when playing (Juul). All content in a representational game will therefore fall into one of three categories. 1. Fiction implemented in rules: This is the most straightforward situation, where the game rules are motivated by the game's fiction. We except to be able to chop a carrot, and the game lets us do just that. Other examples would include cars that can drive, birds that can fly, etc.. 2. Fiction not implemented in game rules: When the fiction suggests a possibility that is not accessible to players. We generally expect to be able to leave a kitchen, and we expect to be able to cut a carrot in any way we like, but the game prevents us from doing so. 3. Rules not explained by fiction: Rules that are difficult to explain by referring to the game fiction[i] – the way Cooking Mama gives the player unlimited replacement ingredients, or the multiple lives in arcade games. Figure 3: Three variations on rules and fiction in video games. Figure 3 illustrates this as a Venn diagram, with some game elements only represented in the game rules, some only represented in the fiction, and some being represented as both rules and fiction. The left side of the diagram covers the many of the amusing examples of video game rules that are not explained by fiction, such as an infinite supply of ingredients previously, the three lives of the traditional arcade game, or even the money given to players when they pass go in Monopoly. I have discussed such examples elsewhere (Juul 5). In the following I will focus on the game elements on the right: on the level of abstraction that distinguishes between the aspects of the game fiction that are implemented in the game rules (middle overlapping section of the diagram), and the aspects that are not (right side of the diagram). Like all non-abstract games, Cooking Mama has such a level of abstraction. The game presents a fictional world, but the game rules only give players access to certain parts of this world, and only allow players to act on a certain level. Game design abstraction can be illustrated through a language metaphor, since language can describe actions with different levels of detail. Going to work can be described as exactly that - "going to work", or it can be listed as a number of individual steps such as "open front door, walk to subway, take subway, leave subway, walk to work", all the way to a description of the concrete path to walk, or even of the individual muscles to activate. In a way, a level of abstraction is a general trait of how we perceive actions, since any action that we take will always entail muscle movements or other biological processes to which we have no conscious access. The question of abstraction is parallel to (but different from) a general issue in representational art: the fact that descriptions of fictional worlds are always incomplete (Pavel 50). Since a description of a fictional world is of finite size, while any world contains an infinite number of facts, there will also be an infinite number of facts that we cannot determine by looking at the art work itself. As an example, it is impossible to determine how many children Lady Macbeth had (Ryan, “Possible Worlds in Recent Literary Theory” 523–533). Any representational art will describe its subject matter in smaller or greater detail, and especially in verbal narrative, we find that this level of detail has changed over time and between genres. For example, the rise of the realist novel shifted the level of description compared to earlier literary forms by describing mundane actions and objects that had otherwise been absent in description. The level of abstraction that I discuss here rather refers to whether game rules implement the imagined fictional world of a game (regardless of the detail by which it was presented). To illustrate the difference between the level of abstraction as it concerns game rules, and the level of detail in a description, consider this passage from the 1983 text adventure game Witness (Infocom). The lines preceded by > are actions taken by the player; the remaining lines are responses by the game.

As can be seen, the description of the game world is sufficiently detailed to include notes about the weather (and the particular quality of the rain). On the other hand, the game rules do not grant the player access to the same weather elements. An element of the fictional world of a game (such as rain in Witness or the table cloth in Cooking Mama) may be or may not be implemented in the programming and rules of a video game. However, the relation between world description and the level of abstraction is rather subtle: given that users fill in the blanks about any fictional world using real-world or fiction expectations (Ryan, Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory), a player can make as detailed assumptions about a cursorily described world as a about one described in excruciating detail. The gap of abstraction between what appears to be possible in the fictional game world and what is actually possible in the game rules is therefore logically the same, regardless of how the world is presented to a player. Yet, in actuality, a player approaching a new game does not go through the process of identifying the game’s level of abstraction from scratch, but builds on the fact that each game genre has its own particular level of abstraction: for example, a racing game always lets players control the steering wheel of a car, but a city simulation generally lets this be beyond the player’s control. Abstraction as Design

Figure 4: Diner Dash: Flo on the Go. (PlayFirst 2006) In the cooking example, any level of detail from selecting the dish, to controlling the muscles of the hand holding the knife can be imagined. However, changing the level of abstraction would make Cooking Mama a different game. For example, PlayFirst’s game Diner Dash: Flo on the Go (Figure 4) is about running a restaurant. Plausibly, the chef in the game is cooking food like in Cooking Mama, but that action is not available to the player. Though the two games could be conceived as being part of the same fictional world, they are completely different games due to their differing levels of abstraction. In effect, a game genre is a level of abstraction; a game genre is a way of distilling a fictional world into a set of actions that the player can perform. This is also why larger franchises such as Star Wars or Harry Potter can lead to the creation of numerous different video games, each in their own genre, each selecting a particular set of actions from their respective fictional universes. Decoding Abstraction

Figure 5: StarCraft (Blizzard 1998) and Age of Empires II (Ensemble Studios 1999) This discussion of abstraction in Cooking Mama and Diner Dash: Flo on the Go is a view of the two games in retrospect, from the vantage point of having played these games for a while. But playing games is actually a process of exploring abstraction. As players, we come to new games and especially new game genres not knowing the level of abstraction. Consider two classic real-time strategy games, StarCraft (Blizzard Entertainment) and Age of Empires (Ensemble Studios) (Figure 5). The initial impression of these two games is very different depending on the player's experience with real-time strategy games. The novice game player will try to make assumptions about the game based on the game's fiction. Age of Empires II has units and a setting that the player can recognize from other media: the knights presumably have some sort of battle function; the catapult is probably for attacks on castles; the people on the fields probably gather food in some way. From the setting, the player has the possibility of making assumptions about the rule structure of the game. But to a player unfamiliar with real-time strategy games, StarCraft (and especially the Zergs pictured here) yields little information about the rules of the game: what are the blue crystals? What do the critters do? This makes Age of Empires II more accessible to new players, because they can use the fiction to make inferences about the rules. The experienced game player can identify the genre of the games above based on the number of units, the placement of resources, the birds-eye view, and the general interface layout. That is, the experienced player identifies this as a game in the real-time strategey genre and uses this to make assumptions about the rule structure of the game, as well as the general limits within which the interaction take place: tell units where to go, but do not deal with the path finding of the individual unit. Deal with battles, but not with making food. Accept that human units can be "built" in a few minutes. However, the experienced game player does not know where the level of abstraction lies in this specific game. Perhaps this is a game that adds political or social structure as new component to the real-time strategy genre? Perhaps in this game, resource gathering units become fatigued? Abstraction of what?In the example of Cooking Mama, I stated that it is a game set in a kitchen, and discussed to what extent this was reflected in the game rules. This relies on being able to compare a set of assumptions about the represented world (a kitchen), with the possibilities that the game offers. In other words, the experience that a game is an abstraction depends on the player identifying what the game is an abstraction of. Consider the game shown in Figure 6. This game features a number of geometrical objects in different colors.

Figure 6: The Marriage (Humble 2006) Rod Humble's experimental game is called The Marriage, and is meant to illustrate the tensions and developments in a marriage, with the two squares representing the partners and the circles representing the external influences upon the relationship. As the author notes, this is not something that players can generally intuit from seeing the game. This is a game that requires explanation. That statement is already an admission of failure. But when working with new art forms one has to start somewhere and it's unfair to an audience to leave a piece of work (even if it’s not successful) without some justification. It's probably some kind of record to have such a small game give hundreds of words of explanation. (Humble) The Marriage can only be perceived as radical abstraction of the workings of a relationship if the player understands that the game represents a marriage at all. An element of communication is integral to representational games: the player must in some way be convinced to see the game as a representation of something. The player can then consider the difference between his or her assumptions about the fictional world and the actions the game actually allows for. Virtual Reality: the Dream of removing the Level of AbstractionGiven that video games have changed quite drastically along with improvements in computing and graphics technology, it could be tempting to assume that the level of abstraction is simply due to technological limitations. Perhaps, given the right technology and sufficient amount of resources, we can make a game that photorealistically represents a kitchen and also simulates it to an arbitrary level of detail? This was the 1990’s dream of virtual reality, or of the Holodeck from Star Trek (Murray): to have a game-like experience without a level of abstraction, a game where anything was possible and everything was simulated to arbitrary detail. In a hypothetical virtual reality Cooking Mama, we would finally be able to make carrots sticks, or even order take-out – just like in a real kitchen. With continued improvements in video game technology and increasing game development budgets, the idea of a hypothetical, perfect simulation resurfaces at regular intervals, but critical voices remain. As game designer Frank Lantz has put it:

Furthermore, the role of abstraction is not simply to make the game different from what it represents, but to make it different for specific purposes. Chaim Gingold has compared game development to the aesthetics of Japanese gardens:

Gingold's view presents abstraction as a way of both making a world, and of making that world readable. Indeed, abstraction can be seen as the process by which any given subject matter is transformed into game form. Consider fighting games: since the genre’s beginning with games like Street Fighter (Capcom) or Karate Champ (Figure 7) (Data East), fighting games were predominantly 2-dimensional. At the time, this was by technological necessity since the hardware was not capable of representing 3-dimensional worlds.

Figure 7: Karate Champ (Data East 1984): 2d in a 2d world. What happened once technology progressed to the point where 3-dimensional worlds could easily be created? Compare Karate Champ to Super Street Fighter IV (Dimps/Capcom) shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Super Street Fighter IV (Dimps/Capcom 2010): a 2d game in a 3d world. Even in this lavish 3-dimensional game world, the fighting is placed on a single axis where the players are always facing directly toward or away from each other.[ii] This can be motivated in several ways – the amount of possible actions is more manageable when players can only attack each other from the front or the back; it makes the game easier to learn; it means that the visuals are more elaborate without making the gameplay too complex. This is an example of an abstraction that remains part of a genre, even when technological advances would allow games to remove an abstraction, in this case the absence of the 3rd dimension. This proves that the history of video games is not simply driven by technological advances. Rather, a genre that is well understood by game players and game designers can remain stable over time regardless of changing technological affordances. Abstraction as Player OptimizationTo play a game is to learn, and to examine that game's level of abstraction. Additionally, games tend to push the player towards optimizing his or her strategy, and that influences the way players perceive a game. As in the discussion of real-time strategy players above, an experienced player may understand the game as a variation on a genre, but a player not used to the genre may use the fiction to understand what type of actions are possible in the game. A study of first person shooter players (Retaux and Rouchier) found that acquiring proficiency in a game was often accompanied with turning down the level of detail of the graphics. It would be possible to make the argument that this constitutes a shift of focus away from the subject matter of the game – the game as fiction – to the game as rules (Juul 139). In certain types of games, this probably is the standard: the novice player begins playing with a focus on the game fiction, and ends up thinking only about the game as an opportunity for optimizing strategies. However, for psychological reasons there is great variation between different games. One of the theories of skill acquisition examines how users learn to separate task-relevant from task-redundant information:

Any game that enforces its goals strongly or is highly competitive, pressuring the player to improve his or her performance, will push the player towards information reduction, towards only thinking about what is relevant for the present task. If the fiction is not relevant for the player's task, it becomes possible for the player to play the game as if it were an abstract game.

Figure 9: Sims 2 (Maxis 2004) To shift the focus away from the fiction means that when thinking about the game, we can plan strategies by considering the abstract rules of the game only, without using the knowledge that we have from the game fiction. In a game like chess, this is straightforward: it is possible to play chess without considering the societal roles of the pieces, because thinking about the societal roles of the pieces is unlikely to be of any help when playing the game. On the other hand, while Sims 2 (Maxis) shown in Figure 9 could theoretically be played as an abstract game containing a number of entities with parameters that had to be optimized ... it is hard to imagine playing the game without thinking about people with emotions[iii]. Incidentally, the way we play Sims is explained by philosopher Daniel Dennett’s concept of the intentional stance: Dennett argues that it is not as much that objects (humans included) have intentionality, but that it simply is more efficient to predict other people’s behavior by considering their possible intentions, than by thinking of them as physical systems or designed objects (Dennett 16–18). And surely, even though we know that Sims 2 contains no actual people but only simplistic simulations thereof, it is much easier to play Sims 2 by thinking of the on-screen characters as having genuine intentions and desires, than by thinking of the game as a mathematical problem. The other interesting aspect of Sims is the game’s focus on quotidian actions such as taking out garbage. A few years ago, it was generally assumed that household chores were too dull a subject to become a central part of a video game. In a historical perspective, The Sims mirrors the appearance of the realistic novel in the later part of the 19th century where, broadly speaking, novels began to describe everyday life rather than heroes and dramatic events. In the video game case, the change is not just a change of description detail (describing hitherto unmentioned aspects of human existence), but that the game implements everyday life in game rules such that the player can make mundane decisions about what furniture to buy, what food to cook, and when to take a nap. The executives at software company Maxis were famously skeptical of the concept when it was proposed by designer Will Wright, but The Sims went on to become the best-selling PC game of all time (Donovan 25). Finally, the player's attitude towards a game cannot simply be reduced to one of optimization: the player may possess a will to fiction; a desire to engage in make-believe. For example, Jonas Linderoth has documented the struggles of a guild in World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment) who had decided to actively avoid any reference to their game-playing as rule-based game, preferring to explain every interface element or out-of-game action (both the left and right sides of the model in Figure 3) by way of elaborate fictional explanations (Linderoth). For example, players who had to temporarily step away from their computers would refrain from employing the standard AFK (away from keyboard) expression, choosing rather to say that they were adjusting their armor, and so on. Space: The unabstractable

Figure 10: SSX (EA Canada 2012): This is not a space. Although Figure 10 may appear to show otherwise, there is no space inside the snowboarding game SSX (EA Canada). There is no snow, there is no snowboarder, there is no mountain, and there is no space. All of these are fictions, but some of them just happen to be partially implemented in the rules of the game: the spatial layout of the mountain, snow, a somewhat abstracted version of normal laws of physics. Rune Klevjer has argued that concerning the issue of space, the rules-fiction distinction outlined earlier "is dangerously close to the breaking point" (Klevjer). He has a case: analytically, we can explain why the space is a fiction, but at the same time it is hardly possible to play the game without perceiving it as space. Space in video games is special because most video games take place in a space, because the space usually is part of the fiction of the game, and because space is at least partially implemented in the rules (belonging to the overlapping middle of the diagram in Figure 3). In the same way that Sims 2 could theoretically be played as an abstract game of numbers, so could SSX: this would involve a long series of calculations determining which different variables were close to each other in value and so on. In practice, this would be a very challenging game that could certainly not be played in real time. Humans are not general purpose calculators: we have limited overall processing power, but specialties in certain areas. It is by comparison straightforward to make a computer program perform long series of complex mathematical calculations, but much more difficult to program a character to navigate a complex landscape in a way that appears intelligent to a human observer. Compared to computers, humans come with amazing spatial skills. This also means that problems which can be solved in a spatial way tend to be solved spatially by humans, and it is therefore hard for a player to abstract from the space in a game. The Game in thereThe level of abstraction determines how we can reason about the world as players. In a story about a hungry person in a kitchen, we would reason that there would be other ways to acquire food than by cooking in the kitchen according to fixed recipes. In a cooking game, we accept that cooking provides the only source of food. As we can see, this marks a difference between regular stories and games: in a story, the limit of a character’s possible actions is our understanding of the fictional world, by whatever logic it follows. For a game, the limit of a character’s possible action is the level of abstraction: the fact that our available actions are always a subset of the actions that would be available with hypothetical full access to a fictional world. This is not as strange as it would first appear, but pertains to the fact that video games are games. In a well-known formulation, Bernard Suits defines games as being about attaining a goal using the less efficient means available (Suits): the high jump would be easier if we could use a ladder; a race would be easier if we could cut across the tracks; soccer would be easier if we could pick up the ball. "To stick a game in there", as Lantz was quoted saying, is fundamentally about reducing the number of possibilities available to the player in order to make a game[iv]. From this perspective, the level of abstraction comes from the root of video games in in non-digital games: the rules that decide what actions are or are not allowed on a soccer or baseball pitch can be considered a type of abstraction, abstractions that make certain parts of the physical world off-limits in a game. The soccer ball can only be handled in certain ways; the baseball player actually runs on a 1-dimensional line with a few discrete bases. The magic circle of games (Huizinga) that delineates what is inside from what is outside the game, is then not just a visible spatial boundary, but can be seen as dividing every single object, action, and player into a component that is part of the game, and a component that is not a part of the game. Soccer removes the ability of field players to touch the ball with their hands, Super Street Fighter IV removes many of the details of actual fighting, and a video game version of soccer is an abstraction of the physical game of soccer. Hence it is rare for players of video game soccer to complain about the inability of field players to capture the ball with their hands. Since soccer identifies this as an off-limit action, we do not expect to find it implemented in video game form. This also explains why we do not find it strange that Cooking Mama prevents us from ordering take-out: as the title suggests, this is a game about cooking, and we therefore accept that our actions are limited to those directly relevant to cooking. Likewise, we accept that we are not free to cut carrots any way we want, since this subsection of the game is specifically about slicing carrots as fast as we can. This demonstrates how we – naturally – interpret game events through the lens of game conventions. When we experience a game event that is not explained by the game fiction, we always have two other strategies available: we can explain the event as being due to the necessities of the rules of the game (left side of Figure 3), or we can assume that some fictionally reasonably action just is not available to us due to the level of abstraction (right side of Figure 3)[v]. The seemingly strange limitations that prevent video game players from making perfectly logical actions, such as cutting carrots into sticks, or ordering take-out, are exactly the limitations that make video games part of the field of games. The level of abstraction may at first seem like a byproduct of technological limitations, but it is in actuality a central component of game genres and player expectations. Video games are a double movement: giving us access to new fictional worlds, then giving us only limited options in those worlds, in order to make a game. ReferencesBioWare. Mass Effect 2. Electronic Arts (Xbox 360), 2010. Video game. Blizzard Entertainment. StarCraft. Blizzard Entertainment (Windows), 1998. Video game. ---. World of Warcraft. Blizzard Entertainment (Windows), 2004. Video game. Capcom. Street Fighter. (Arcade), 1987. Video game. Data East. Karate Champ. (Arcade), 1984. Video game. Dennett, Daniel C. The Intentional Stance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989. Print. Dimps/Capcom. Super Street Fighter IV. Capcom (Xbox 360), 2010. Video game. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. Lewes, East Sussex: Yellow Ant, 2010. Print. EA Canada. SSX. EA Sports (Xbox 360), 2012. Video game. Ensemble Studios. Age of Empires. Microsoft (Windows), 1999. Video game. Fludernik, Monika, Towards a “Natural” Narratology. London, UK: Psychology Press, 1996. Print. Gingold, Chaim. “Miniature Gardens & Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, & Worlds.” 2003. Web. 2 May 2012 <http://levitylab.com/cog/writing/thesis/>. Haider, Hilde, and Peter A. Frensch. “The Role of Information Reduction in Skill Acquisition.” Cognitive Psychology 30.3 (1996): 304–337. Print. Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens, A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1950. Print. Humble, Rod. The Marriage. (Windows), 2006. Video game. May 2 2012 <http://www.rodvik.com/rodgames/marriage.html>. Infocom. Witness. (DOS), 1983. Video game. Juul, Jesper. Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005. Print. Klevjer, Rune. “What Is the Avatar?” 2006. Web. May 2 2012. <http://folk.uib.no/smkrk/docs/RuneKlevjer_What%20is%20the%20Avatar_finalprint.pdf> Lantz, Frank. “Game Developers Rant II.” San José, CA, 2006. Web. May 2 2012. < http://crystaltips.typepad.com/wonderland/2006/03/gdc_game_develo.html> Linderoth, Jonas. “The Struggle for Immersion. Narrative Re-framing in World of Warcraft.” Proceedings of the [Player] Conference. Ed. Olli Leino, Gordon Calleja, & Sarah Mosberg Iversen. IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. Print. Maxis. The Sims 2. Electronic Arts (Windows), 2004. Video game. Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. MIT Press, 1998. Print. Nintendo. Donkey Kong. Nintendo (Arcade), 1981. Video game. Office Create. Cooking Mama. Taito (Nintendo DS), 2006. Video game. Pajitnov, Alexey, and Vadim Gerasimov. Tetris. (DOS), 1985. Video game. Pavel, Thomas G. Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989. Print. PlayFirst. Diner Dash: Flo on the Go. (Windows), 2006. Video game. Retaux, Xavier, and Juliette Rouchier. “Realism Vs Surprise and Coherence: Different Aspect of Playability in Computer Games.” Manchester, 2002. Print. Rovio Entertainment. Angry Birds. Chillingo (iOS), 2009. Video game. Ryan, Marie-Laure. “Possible Worlds in Recent Literary Theory.” Style 26.4 (1992): 528–533. Print. ---. Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991. Print. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004. Print. Suits, Bernard Herbert. The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1978. Print. AcknowledgementsAn earlier version of this article was presented as A Certain Level of Abstraction at the DiGRA conference, Tokyo, September 2007. Thanks to Marie-Laure Ryan, Jan-Noël Thon, and Nanna Debois Buhl for comments. [i] It is of course possible to create a fictional motivation for any game rule, but the point is that we often do not. Players do not explain the three lives of Mario in Donkey Kong (Nintendo) as due to Mario being reincarnated, but by referring to the rules: otherwise the game would be too hard (Juul 4). [ii] It can be argued that 3d fighting games lack certain types of ranged attacks like fireballs, that would have appeared incongrous since such 3d games often rotate the 2-dimensional axis that the opponents play on, and that ranged attacks would therefore either have to magically move with this rotating axis, or it would be possible to sidestep such an attack. I am indebted to Charles Pratt for this observation. [iii] A player with autism would perceive Sims as a different type of game, since the player would lack an existing set of skills for processing people interaction and emotional issues. [iv] A similar argument is made by Salen & Zimmerman (138). [v] This argument, that games allow for interpretation strategies that refer to the medium itself, has many parallels in the theory of narrative. For example, Monika Fludernik’s concept of narrativization describes “a reading strategy that naturalizes texts by recourse to narrative schemata” (Fludernik 25). |